Update 2025-09-24: I broke this post up into two posts, one here and one on the VocalPy developer’s blog, based on feedback from folks in the US-RSE and pyOpenSci communities: Ben Fulton, Hector Correa, Kris Armeni and Warrick Ball, and Felipe Moreno.

Update 2025-12-23: Revised again.

In this post I hope to convince you that you should care about domain-driven design. It falls into the category of “me writing about how my thinking has evolved about research and software”.

You might read about domain-driven design and think “I already do this. Why do I need to name it and formalize it?” I am not claiming this is a radical new idea. What I hope to convince you of is that, sure, domain-driven design is just as obvious as it sounds, but you should be thinking about it more anyways.

So: first I’ll introduce domain driven design, then I’ll explain why I think it’s worth thinking about it more, even if you think it’s something you already do.

What is domain-driven design?

First, let me introduce domain-driven design, and tell you why you might care about it. Sometime in 2022-2023, I read Domain-Driven Design by Eric Evans, and I got really excited about it. (You can get it from bookshop.org here, and if you’re feeling dangerous you can probably find a PDF of it on a random GitHub repository.) I ended up reading it because I had been reading Architecture Patterns with Python, and they mentioned it in the introduction.

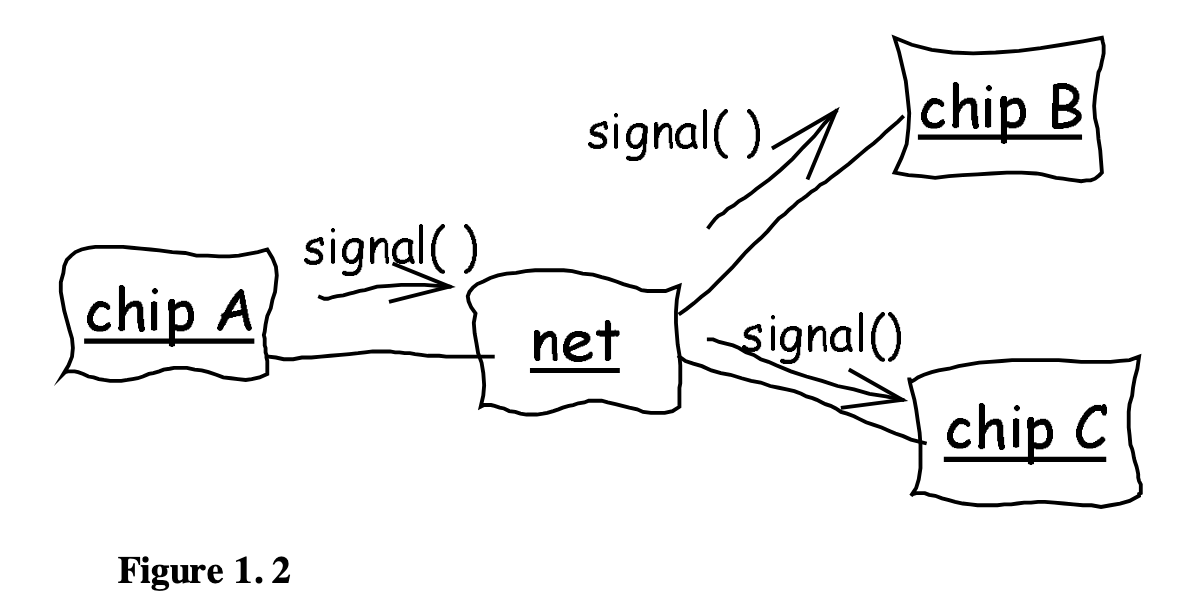

If you do nothing else, read the first chapter of Evans’ book, where he relates the story of how he worked with some electrical engineers to design software they would use to design printed circuit boards (AKA PCBs).

At the beginning, he makes mistakes. He tries to understand their jargon word-for-word. Then he asks them to specify in detail what they think the software should do. Neither of those approaches were ever going to work well. Finally he hits upon the idea of asking them to draw out diagrams of their process and how the software should interact with it. These are simple, rough box and arrow sketches as he shows.

Notice what is happening here: this is not just a developer creating a UML diagram to show to other developers. This is software engineers and domain experts developing a pidgin language together. They use this pidgin to talk about the domain problem they are trying to solve with software.

It’s an interesting story for a couple of reasons. First of all, you have a feeling that he is almost an anthropologist, going into this unfamiliar tribe of electrical engineers so he can learn their culture. I think this is a familiar feeling for anyone who has tried to translate some real-world domain into software, even if it’s part of a culture they feel like they belong to. Second, you really get a feel for his process.

If you have ever gone through the process of designing software for some real-world domain, I bet the story really resonates with you. Or, you know what? I’ll dare to say that, even if you have only ever written nerdy software tools for the domain of other software nerds, you still might find that the story resonates with you. Software engineering is a domain, after all. (I’ll return to this point below.)

At this point, you might be thinking, “write code in terms of your domain, yeah, sure, everybody does that”. I got really excited reading this stuff, and told people about it at the job I had at the time. I made a big deal of presenting parts of the book, and talking about how we could use this approach for what we were working on. And I got this very underwhelmed response of “Yeah, we sort of already do that. Aren’t you just describing object-oriented programming?” Yes, but no! I’ll come back to the “no, we aren’t doing that” below, but first, the yes. We should realize this is what we’re already doing and be very explicit about it! The domain should be at the front of our mind at all times, and we only should be iterating on the design of our software insofar as it relates to the domain!

Now, the “but no”: domain-driven development isn’t just thinking about the domain. Yes, we all think of the domain when we write our code, more or less subconsciously. But Evans advocates for a specific development process. He says this process is required for his approach to design to work. He sees it as a form of extreme or Agile programming. If you’re not familiar with those, the important thing to know here that they are more iterative than previous approaches, that focused on “elaborate development methodologies that burden projects with useless, static documents and obsessive upfront planning and design”, as Evans puts it. Instead, he focuses on writing code that has a bare bones implementation he can test right away. “Development is iterative.” Of course, this is one place where Python, my main programming language, shines. It’s really easy to iterate interactively in a Jupyter notebook with a bare-bones implementation of your sketch of an API. Of course, later you should do some proper engineering instead of living in Jupyter notebooks, so you don’t have to worry about someone giving a preachy conference talk that condemns you for your naughty programming practices.

Evans’ other requirement for the development process is that “[d]evelopers and domain experts have a close relationship.” If you are a researcher who programs, well, hopefully you already have a close relationship with yourself. And with your collaborators and colleagues. This second requirement naturally gives rise to one of the key ideas from the book, that of ubiquitous language. This is what I called a pidgin above. It’s a language that the domain experts and software developers arrive at together through the iterative process of development. The words in this ubiquitous language correspond to key concepts in the domain that the software needs to capture, the things that developers and domain-experts realize they should focus on, as they iterate. Ubiquitous language “embeds domain terminology in the software systems we build”, as Martin Fowler puts it in this post. It’s this continous process of developer and domain expert iterating together that really appeals to me.

Domain-driven design is not new, and you should think about it more anyway

Ok, so now let me circle back around, talk about why, sure, domain-driven design is not a new idea (as Evans himself acknowledges right at the start of his book), and why you should be doing it, or doing even more of it. This is where I come back to the “no” part of “Do we already do this? Yes and no.” As you can tell, I’ve gotten this reaction before: “so, yeah, we already do that”.

If that’s so, then show me the doodles! Like Evans’ box-and-arrow diagrams above. Show me your mental model of your domain. Put it in your docs! Let me read it, let me actually see these schematics, even if they are just doodles, it helps me to know how your thought process evolved. All I can see right now is this insurmountable mountain of code. I don’t even know where the hiking trail starts so that I can scale the mountain! I know that there are examples of people doing this, e.g., in the scientific Python community where I spend most of my time, but I think it’s fair to say that this is not the norm. (Thank you to Warrick Ball from US-RSE who shared a good example of domain-driven design from his aims3 docs) I don’t know that I have ever seen diagrams showing how the design evolved, as part of an iterative development process. I can’t help but feel like that’s exactly the sort of thing that could help people get up to speed on how the code works.

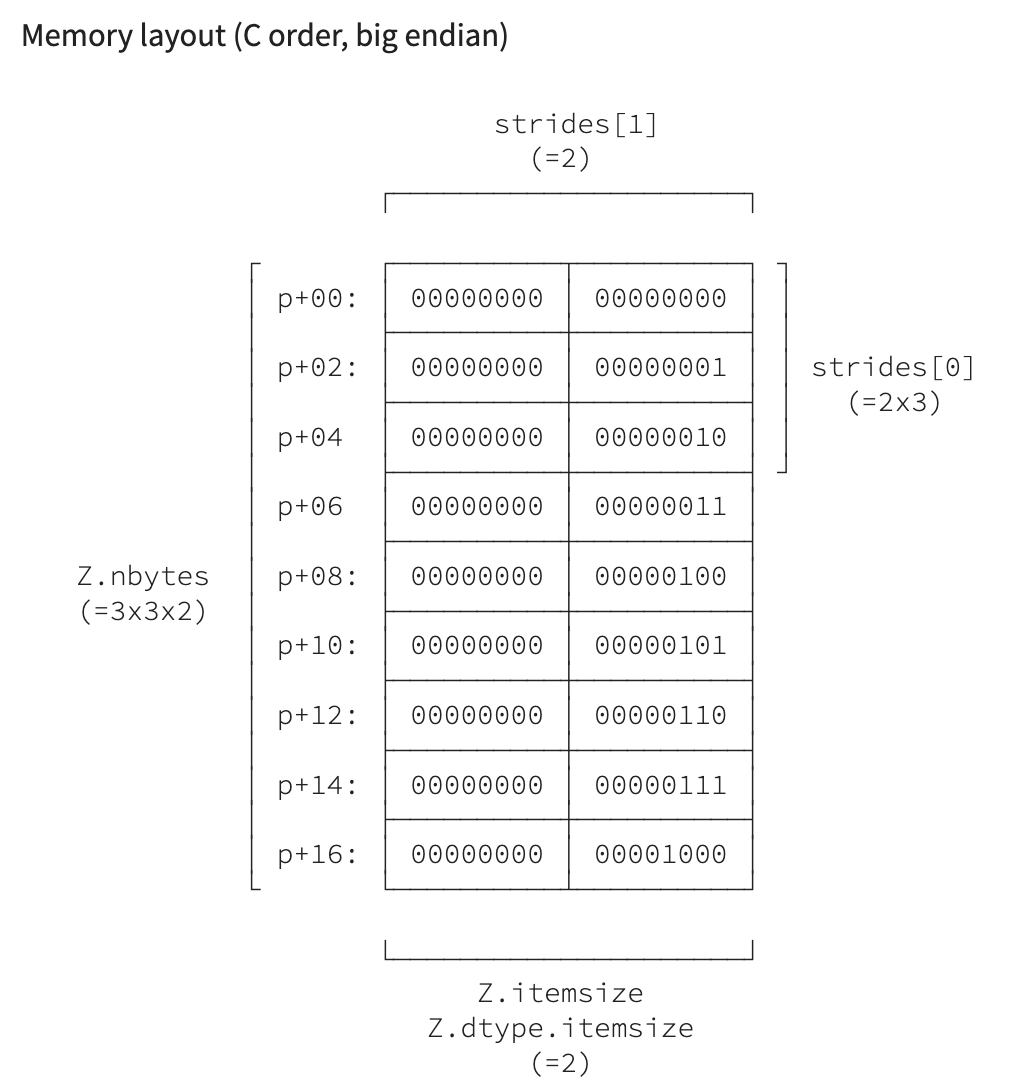

Just to make this real concrete, I’ll give one example from my world of scientific Python. With this example, I want to show first of all that, yes, people definitely work this already, even if they don’t call it domain-driven design. And, second, that we could make this design process easier to find, and use it in a way that makes code easier to understand. My example is: the numpy n-dimensional array, that we’ll call ndarray for short. This is the core abstraction tha makes all of scientific Python possible. How do the developers of NumPy conceive of the ndarray? Of course, if you go to the “Getting Started” section, you can get a written introduction, arguing for why we need an n-dimensional array in Python, and showing you some code snippets. Great. But I want a drawing. Like the doodles above. A picture is worth a thousand words. So if I make it down to the bottom of that page, I can find a link to the NumPy reference, and there finally if I click on array objects, I can find this picture:

I think a diagram like this would help a beginner understand what an ndarray is!

And I can’t be the only one, since Nicolas Rougier has written a whole book about going from Python to NumPy, and he starts the book with these kinds of diagrams.

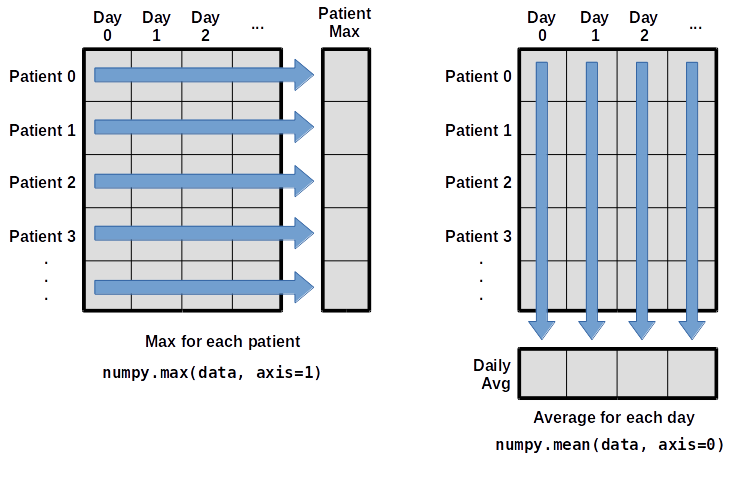

Similarly, the Software Carpentry course Programming with Python uses a diagram to illustrate how numpy.max function works. (If you look up the numpy.ndarray.max method, you’ll be directed to the numpy.max page.)

Every time I have to remember which axis is which, I find myself wishing the NumPy docs had a diagram like this.

More to my point above: I want to know how the design of the ndarray evolved! How did a group of developers come together from packages like numeric and arrive at a new design? What did they recycle, and what did they throw away? If I look at the “Under-the-hood documentation for developers”, I don’t find any of this. Of course you can argue that this might seem like too much detail for developer docs. If I’m a developer and I’m just trying to figure out how to subclass ndarray, do I really need to know the whole history of your library? Yet I know this stuff exists, on GitHub issues for example, as part of the design and development process. So maybe it’s worth keeping a record of how things evolved somewhere in your documentation? And making that more readable with diagrams.

Please let me emphasize that I am not trying to call out Numpy here, or make an example of them, or anything like that. I know how much work and how many volunteer hours go into maintaining NumPy, and building the community around it. A lot of those people are my friends from conferences. I just want to give some sort of concrete examples. In their defense, we can notice that NumPy is so widely used that it was easy for me to find these examples. I am just wondering what else we can do as research software engineers to make libraries more approachable. Maybe it would help prevent snarky young kids from writing blog posts like this.

Not to belabor the point, but I’ll stick in a couple more examples of architecture diagrams from docs that I have noticed since I’ve been revisiting this idea. Two things I want to say here: the first being that, while it’s good that these diagrams exist, you often have to dig to find them. So, again, I’m not saying I have a revolutionary idea; I’m just wondering if we could surface this stuff a little more.

Here for example is a diagram from the “internals” section of the dask docs on scheduling, illustrating the two types of schedulers:

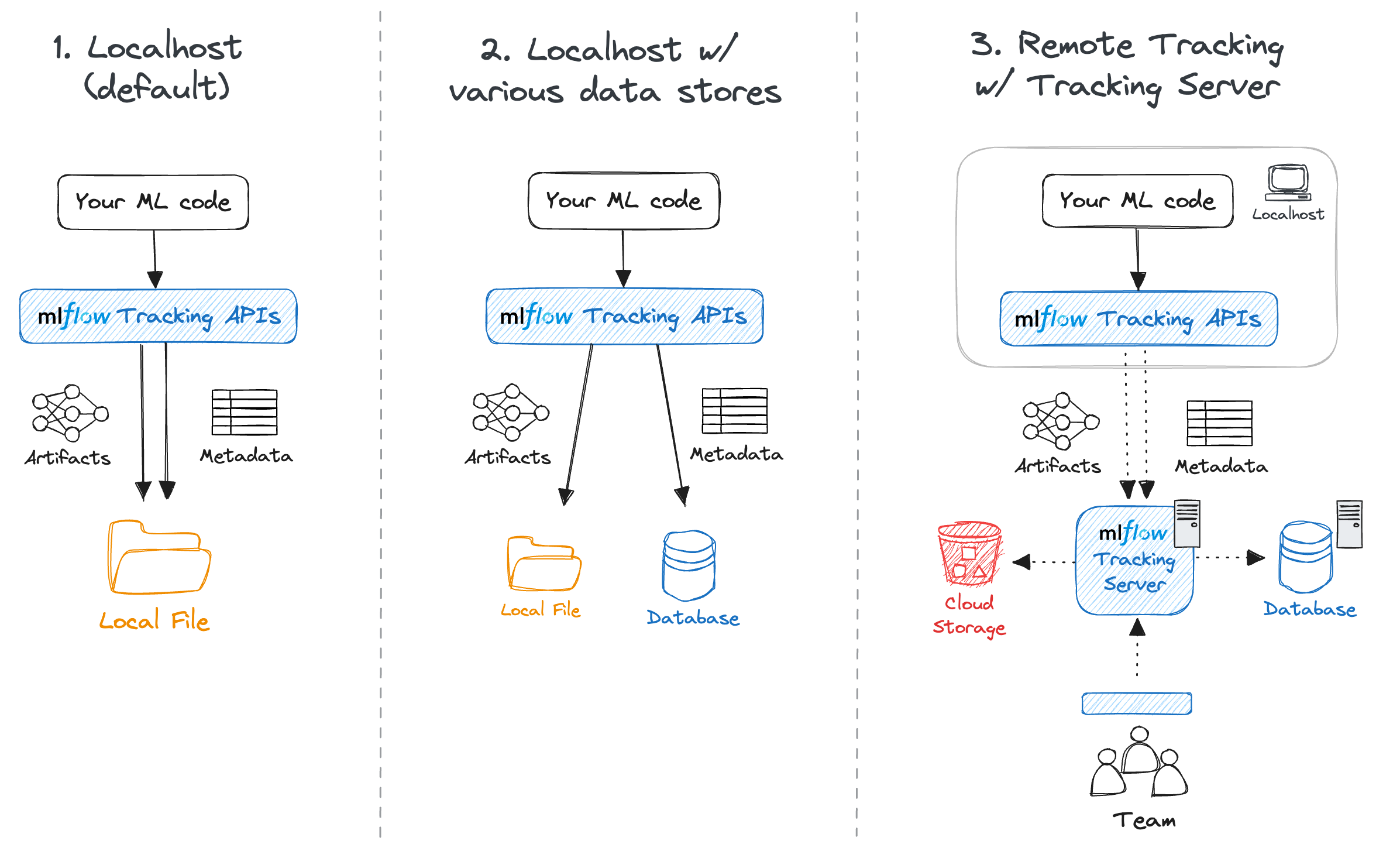

And here is a diagram from the “architecture” section of the mlflow docs, illustrating common setups:

The second thing I want to say here is: I think you can see these diagrams differently. They show software engineers doing domain-driven design. At the risk of sounding like I’m preaching that “everything is domain-driven design”, I’ll say that this looks to me now like software engineers designing for a domain using an ubiquitous language, one spoken by the other engineers they work with, and the engineers that use their libraries. They speak in terms of “abstractions” and “architectures”. (This is me returning to the point above about software engineering being a domain.)

Reprise: domain-driven design is such an old idea that it’s in SICP

Lastly, let me reiterate, I know these ideas are not new. I now know for sure they’ve been around longer than Eric Evans’ book, because I have been attempting to read yet another book, Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs, AKA, SICP. I ended up finding domain-driven design in SICP, and having to admit to myself that, yeah, this idea has been around forever. When I got to chapters 2 and 3, there I saw that we were talking about data abstraction and designing programs for modeling. Sound familiar? Let me quote you this bit from chapter 3:

One powerful design strategy, which is particularly appropriate to the construction of programs for modeling physical systems, is to base the structure of our programs on the structure of the system being modeled. For each object in the system, we construct a corresponding computational object. For each system action, we define a symbolic operation in our computational model. Our hope in using this strategy is that extending the model to accommodate new objects or new actions will require no strategic changes to the program, only the addition of the new symbolic analogs of those objects or actions. If we have been successful in our system organization, then to add a new feature or debug an old one we will have to work on only a localized part of the system.

Well there it is, domain-driven design in a nutshell.

I hate to end on an appeal to authority, but I feel like, if a book as venerable and time-honored as SICP talks about domain-driven design, if the authors think it’s worth discussing in the introductory sections of their chapters, then it must be an idea worth keeping in mind. (Such is the state of computer science that I am calling a book that’s less than half a century old “time-honored”.) I hope I’ve convinced you to think about domain-driven design just a little more.

Addendum

I wrote a follow-up post related to what I’m learning from SICP: “Have a working model when you code”. I broke that off into another post to make extra sure I don’t sound like a rabid revolutionary claiming that everything is domain-driven design. I’m afraid I am tiptoeing towards a breakaway sect of programmers here.

But I have to say that thinking about domain-driven design has also got me seeing overlap with ideas like programming as theory building, and domain-specific languages as an alternative to magical, god-like AI “agents” that do all the intellectual heavy lifting for software developers (and anyone else who does any kind of creative thinking for a living). See this quote from the introduction to “A Small Matter of Programming” (the book I just linked to, that considers task-specific languages, among other things):

(Thank you to Alistair Davidson who I saw post about this book on Bluesky, I’m recycling their screenshot and alt text.) I think that ideas about software as the output of a human-driven, theory-based process put the lie to the notion that Large Language Model-driven development will end software engineering as we know it sometime soon. LLMs can’t think, they can’t theorize, no matter how many names you steal from cognitive science to give to the underlying math. Yes, as a (lapsed) cognitive scientist, I think “chain of thought reasoning” is an offensive name for what is essentially Viterbi decoding with delusions of grandeur. But I’ll save those thoughts for yet another blog post.